|

||

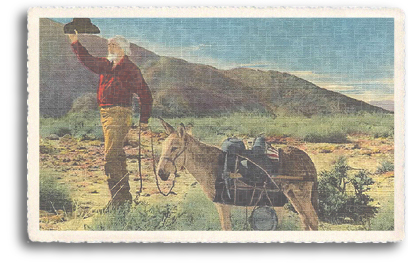

The Burro, Domestic and Wild The Burro, Domestic and WildThe word Burro is derived from the Spanish word “borrico” meaning donkey. Therefore, a burro is a small donkey, often used as a pack animal. A male donkey (jack) can be crossed with a female horse to produce a mule. Burros come in many different colors including red, red roan, pink, blue, black, brown, and paint. By far, the most common color is grey with a white muzzle and white underbelly. Burros average 11 hands high (44") and weigh about 500 pounds at maturity. Burros are adapted to marginal desert lands, and have many traits that are unique to the species as a result. They need less food than horses. Overfed Burros can suffer from a disease called laminitis. Unlike horse fur, burro fur is not waterproof, and so they must have shelter to protect them from rain and snow. Burros have developed very loud voices to keep in contact with other Burros of their herd over the wide spaces of the desert. Burros have larger ears than horses to hear the distant calls of fellow Burros, and to help cool the burro’s blood. The tough digestive system of the burro can break down inedible vegetation and extract moisture from food more efficiently. Burros can defend themselves with a powerful kick of their hind legs. It is commonly believed that the ancestor of the modern Burro (or donkey) is the Nubian subspecies of African Wild Ass, a medium sized donkey with a grey and white coat, stripes on back and legs and a tall, upright mane with a black tip. The African Wild Ass was domesticated around 4000 B.C. The donkey became an important pack animal for people living in the Egyptian and Nubian regions as they can easily carry 20% to 30% of their own body weight and can also be used as a farming and dairy animal. By 1800 B.C., the donkey had reached the Middle East Syria produced at least three breeds of donkeys, including a saddle breed with a graceful, easy gait, which were favored by women.  In 1495, the donkey first appeared in the New World. The four males and two females brought by Christopher Columbus gave birth to the donkeys which the Conquistadors rode as they explored the Americas. Shortly after America won her independence, President George Washington imported the first mammoth jackstock into the young country. Because the jack donkeys in the New World lacked the size and strength he required to produce quality work mules, he imported donkeys from Spain and France. Despite these early appearances of Burros in American society, the Burro did not find widespread favor in America until the miners and gold prospectors of the 1800s. In the barren, nearly water-less hills, the Burro adapted well and became indispensable to prospectors. Burros were used as pack animals for the prospectors, worked in the mines hauling ore, and carried supplies, water, and even machinery into desolate mining camps. Their sociable disposition and fondness for human companionship allowed the miners to lead their Burros without ropes; they simply followed behind their master. The lone prospector and his trusty pack burro became a legendary symbol of the old west. With the introduction of the steam train, these Burros lost their jobs and many were turned loose into the American deserts. Descendants of these Burros can still be seen roaming the Southwest in wild herds to this day. By the early 20th century, the Burros began to be pets in the United States and some other wealthier nations, while remaining an important work animal in many poorer nations. The Burro as a pet is best portrayed by the appearance of the miniature donkey in 1929. Robert Green imported miniature donkeys to the United States and was a lifetime advocator of the breed. Mr. Green is perhaps best quoted when he said, “Miniature donkeys possess the affectionate nature of a Newfoundland, the resignation of a cow, the durability of a mule, the courage of a tiger, and the intellectual capability only slightly inferior to man’s.” Standing only 32-40 inches, many families were quick to recognize the potential these tiny equines possessed as pets and companions for their children.  Although the Burro fell from public notice and became viewed as a comical, stubborn beast who was considered cute at best, the Burro has recently regained some popularity in North America as a mount, for pulling wagons, and even as a guard animal. Some standard species are ideal for guarding herds of sheep against predators since most Burros have a natural aversion to canines and will keep them away from the herd. Although the Burro fell from public notice and became viewed as a comical, stubborn beast who was considered cute at best, the Burro has recently regained some popularity in North America as a mount, for pulling wagons, and even as a guard animal. Some standard species are ideal for guarding herds of sheep against predators since most Burros have a natural aversion to canines and will keep them away from the herd.Burros have a reputation for stubbornness, but this is due to some handlers’ misinterpretation of their highly-developed sense of self-preservation. It is difficult to force or frighten a Burro into doing something it sees as contrary to its own best interest, as opposed to horses who are much more willing to, for example, go along a path with unsafe footing. Actually, Burros are just very cautious. When placed into an unfamiliar situation, a Burro will stand its ground and ponder its predicament. Pulling or pushing on the animal does little to help them make up their minds. Although formal studies of their behaviour and cognition are rather limited, Burros appear to be quite intelligent, friendly, playful, and eager to learn. They are many times fielded with horses due to a perceived calming effect on nervous equines. If a Burro is introduced to a mare and foal, the foal will often turn to the Burro for support after it has left its mother. Once a person has earned a Burro’s confidence, they can be a willing and companionable partner and very dependable in both work and recreation. Burros are also popular for giving rides to children in holiday resorts or other leisure contexts. Most Burros (probably over 95%) are used for the same types of work that they have been doing for 6,000 years. Their most common role is for transport, whether riding, pack transport, or pulling carts. They may also be used for farm tillage, threshing, raising water, milling, and other jobs.  Wild Burros Wild BurrosA Wild Burro is an unbranded, unclaimed, free-roaming burro found on Bureau of Land Management (BLM) or U.S. Forest Service (USFS), administered rangelands. The greatest number of Wild Burros live within the arid deserts of the Southwest. Wild Burros are descendants of pack animals that wandered off, or were released by prospectors and miners. With kindness and patience a Wild Burro can be trained for many uses. Due to their gentle nature, Wild Burros can be used as companion animals for high spirited domestic horses. In addition, Wild Burros are social, yet very protective animals. Because of this trait, they are very effective in predator control and are often used as guard animals to protect sheep and goats. Wild Burros are known for their sure-footedness, strength, and endurance and are used as sturdy pack animals for backpackers and hunters. People also use Wild Burros as riding animals and to pull carts or wagons. The greatest advantage to adopting a Wild Burro, is that they make excellent family pets. Every Wild Burro is different. Like people, they have their own personalites. Burros recently removed from public rangelands are not used to people. As an adopter, the challenge is to develop a trusting relationship with the Wild Burro. The Wild Burro was first introduced into the Desert Southwest by Spaniards in the 1500s. Wild Burros have long ears, a short mane and reach a height of up to five feet at the shoulders. They vary in color from black to brown to gray. Wild Burros can survive in a wide variety of desert habitats as long as they are within 10 miles of drinking water. Originally from Africa (where they were called the Wild Ass), these pack animals were prized for their hardiness in arid country. They are sure-footed, can locate food in barren terrain and can carry heavy burdens for days through hot, dry environments. Wild Burros can tolerate a water loss as much as 30% of their body weight, and replenish it in only five minutes of drinking. In comparision, humans require medical attention if 10% of body weight is lost to dehydration and require a full day of intermittent drinking to replenish this loss.  Wild Burros feed on a variety of plants, including grasses, Mormon Tea, Palo Verde and Plantain. Although some moisture is provided by these plant materials, Wild Burros must have drinking water throughout the year. They can usually be seen foraging for food during daytime, except for summer, when they will forage only at night and in the early morning. Wild Burros feed on a variety of plants, including grasses, Mormon Tea, Palo Verde and Plantain. Although some moisture is provided by these plant materials, Wild Burros must have drinking water throughout the year. They can usually be seen foraging for food during daytime, except for summer, when they will forage only at night and in the early morning.Female Wild Burros give birth to one colt each year, which grows to an average weight of about 350 pounds. Since the Wild Burro has no natural predator, competitor or common diseases, most young Burros reach maturity and may live as long as 25 years in the wild. Early prospectors relied heavily on Burros as they trekked long distances across the deserts in search of gold and silver. Many of these Burros survived, even though their owners perished under the harsh desert conditions. Many more Burros escaped or were released during the settlement of the West. Because of their hardiness, Wild Burros have thrived throughout the North American deserts, and their numbers have increased to perhaps 20,000. Special Programs for Wild Burros Wildlife biologists maintain that the proliferation of Wild Burros has disrupted the natural order of desert environments and is responsible for the destruction of many native plants and animals. Because they so successfully compete for limited water and food resources, Wild Burros are blamed for the reduction of some native animal populations like the Bighorn Sheep. Programs are now in place, administered by the National Park Service and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), to control Wild Burro populations in the Desert Southwest. The BLM manages about 42,000 wild horses and burros that roam public lands in the West under the Wild Free-Roaming Horse and Burro Act of 1971. This law mandates the protection, management and control of wild, free-roaming horses and burros on public lands at population levels that ensure a thriving ecological balance. The BLM captures and places about 9,000 horses and burros up for adoption each year under its National Wild Horse and Burro Program. The Wild Free-Roaming Horse and Burro Act of 1971, gave the Department of the Interior (BLM) and the Department of Agriculture (USFS) the authority to manage, protect, and control Wild Burros on the nation's public rangelands in a way that ensures healthy herds and healthy rangelands. Federal protection and a lack of natural predators resulted in thriving Wild Burros that grow in number each year. BLM monitors rangelands and Wild Burro populations to determine the number of animals, including livestock and wildlife, the land can support. Each year BLM gathers excess Wild Burros from areas where vegetation and water could be negatively impacted by over use. These excess animals are offered for adoption to qualified people through BLM's Adopt-a-Horse or-Burro Program. From 1973 through 1999, BLM has used this popular program to place more than 25,000 Wild Burros into private care. Wild Horse and Burro Adoption Back to Plants & Wildlife |

||

Home | Food | Lodging | Merchants | Services | Real Estate | Art & Galleries | Entertainment | Recreation Ski Areas | Mind-Body-Spirit | Taos Information | Local Color | Taos Pueblo | High Road to Taos | Taos Plaza | Ranchos de Taos Scenic Beauty | Day Trips | Chili | Special Events | Taos History | Multicultures | Museums | The Enchanted Circle The Wild West | Taos Art Colony | Plants & Wildlife | Counterculture | Turquoise | Architecture | Features | About Us | Get Listed! Taos Unlimited Trading Post | Photo of the Week | Link of the Month | Taos Webcams | Taos Weather | Testimonials | Guestbook Taos A to Z | Movie Locations | Sitemap | Taos Unlimited Blog | Aimee & Jean's Story Blog | Contact Us | Santa Fe Unlimited |

||